This is the third part of our discussion on Deuteronomic Theology. You can read the first and second discussion posts here:

Deuteronomic Theology Part I (Deuteronomic Theology):

Deuteronomic Theology Part II (Deuteronomic History):

http://look-ing-up.blogspot.com/2019/03/deuteronomic-history-vic-jethro-rachmadi.html

Let us open to Deuteronomy 4:15-34

Covenental life is a central topic in the lives of chosen people, and it is an important basis in Deuteronomy. In this part, we will discuss what God means by a covenant. It is important for us to explore this concept repetitively because we tend to extreme our relationship to either side of the poles. A covenant is a covenantal relationship, which involves two or more parties, consisting of both relational and covenantal aspects. Yet we often separate these two concepts in our daily application. When we sign a contract, we assume that both parties do not have any personal relationship. A personal relationship for us consists of freedom and spontaneity and is absent from regulated rules jotted down on a written contract. But the Bible says that a covenant transcends this narrow category. For in Deuteronomy, we see that our relationship with God is so intimate and private, and yet our demands exceed those of a professional contract. Therefore, we must understand our relationship with God along with its complexity.

Moses used three pictures to show this concept clearly. We always connote our relationship with God with love and faithfulness, but in this part of the scripture, we see jealousy, perversion (idolatry), and consuming fire. Through these three points, we will discuss more in depth about our relationship with God.

JEALOUSY

Richard Dawkins claimed that Christianity must be disposed of, because of this annoying "fictional" character described in Deuteronomy 4:21-24. Not only is He a jealous character, but He takes pride in His jealous attribute. Before we move on, we have to be able to differentiate between jealousy and envy. To envy is to covet (egoistic), but to be jealous is to be possessive (also egoistic and self-centered). The difference is that to envy, is to covet something that others own, but to be jealous is to be possessive towards what one owns. Therefore, the Hebrew and Greek Bible use the terms envy and jealousy interchangeably (Hebrew: qannah/qinnah; Greek: zelos).

Is God's jealousy here the same as envy then? Did Dawkins speak of truth? Is God depicted as an annoying character here? Absolutely not. There is a distinct difference in the Hebrew language. Our differentiating tool is phenomena, while the Hebrew's differentiating tool is in who does it. Though based on the same root word, qinnah is used specifically for human (mentioned 32-44 times in the Bible), while qannah is for God (mentioned 6 times in the Bible). The Bible's differentiating tool is not in its phenomena or the jealousy level a person possesses but in the doer. Therefore, we ought not to view God's jealousy as a negative concept. After all, the positivity in our jealousy is very evident. What kind of jealousy is positive? As parents, when we see our children behaving badly, we rise to anger, which is caused simply by our love towards them. It is easier to explain this in the English language because they have the terms for and against. For instance, are you for or against the nuclear plant? When we are jealous of a person, what is important is to ask the question of whether we are angry with that person, or angry for that person.

Anger is not a sin in and of itself, for anger does not collide with a relationship. If you are engaged in a relationship, you will experience anger. If you have never been angry with a person, it means you do not have any relationship with him. The opposite of love is not anger nor hate, but apathy.

Why then does the picture of anger in our daily life so different than the anger Bible depicts? Because we have never seen true love. Being in our sinful nature, our love is stained with self-centeredness, as we love others to fulfill our personal needs. We are often more hungry than being in love. We could love something immensely, but only for us to consume. If you truly love a tree, you would not loot its twigs, fruits, and wood, but you would water it. Therefore, it is impossible for us human to create positive jealousy, because our anger is always because of the object, and not for the object. We rise to anger because their sins humiliate and inflict us.

Thus, the classification is not between envy and jealousy, but in the doer. The aspect of corruptness is ever present when we are jealous, not because there is absolutely no aspect of angry for the object, but because there is always an aspect of anger because of the object.

Yet God's jealousy purely consists of anger for those whom He loves. We must be thankful if our relationship with God is full of God's anger because it only shows how much He cares and loves you. CS Lewis wrote that a God who is never satisfied with you only shows that He is a God who loves you, like an artist who considers his art always lacking and in need of correction. God is never satisfied. Demanding a God who could be satisfied is demanding Him to stop loving us.

Now you have seen how positive God's jealousy is. The drop rate in a theological seminary is the highest among all schools. In my previous accreditation, my professor told me that the drop rate of 20-25% in a theological seminary is very common. But in our theological seminary, there must usually be a mistake or a sin which a dropped out student committed during his study, and very rarely due to health issue problem. And every time there was a student being dropped out, the other students would weep, not because of his sins, but our sins. It did not matter what the dropped out student did, what mattered most was the fact that we were aware of his sins since the beginning and refused to confront him. And we did not confront him not because we fear to offend him, but because we simply did not care. Or frankly speaking, our care towards our own feelings mattered more than our care towards him.

Hence, God's jealousy towards men is a significant declaration. God is very committed to our well-being. This is the first point.

IDOLATRY

This second point is mentioned frequently throughout verses 15-23. But before we dig deeper into those verses, we have to set one thing straight: verses 16-19 are especially interesting, this part reminds us of what idolatry is. The purpose of these verses is to show what could be considered gods, and the answer is everything! The purpose of these verses is not to instruct what we should not create, but to instruct that we should not create everything from A to Z. Verse 19 gives an interesting definition, "an idol is not just everything, but something that is God-given". Meaning, an idol is actually something good, because all things God-given is good. In fact, it is a good thing that could be transformed into an idol, and the better it is, the better the idol it will make.

For example, in disciplining your child, you remind them not to play video games for hours so that they would be the number one in their class and become an achiever. Yet, according to the Bible, this aspiration to be the number one and to be an achiever could even be a better idol than hours playing the video game. When your child is all grown up, performance and ranking become his life's goal, by doing so, he abandons his wife and children, he belittles relationships that do not benefit him, all these for the sake of his performance. Because when he plays video games, everyone around him despises his action, and he knows himself that his addiction to video games is bad. Contrarily, by becoming a workaholic, many companies would contact him, offering him jobs. Let this be a reminder for us all that idolatry is not in the object, but about where we rank that object within our hearts. Augustine introduced the idea of ordo amoris (the order of love). If we place the object we love higher than God in our ordo amoris, and if it fills our life, replacing God's position, the object has become our idol. Read more about ordo amoris here: http://look-ing-up.blogspot.com/2017/09/a-double-victory.html.

Idolatry is when we consider an object to be most effectual in our lives, including most effectual in creating grief and resentment. Your idol is not only something that delivers you the most joy, but also something that delivers you the most resentment. Your idol is the most effectual object in your life as it places the highest ranking in your ordo amoris.

The next point which I wish to share is how Moses stated idolatry as a corrupt act (verse 16), which in Indonesian is translated as a decaying act. Idolatry destroys and decays us. We like to think that Moses used this term merely as a metaphorical language, that committing idolatry is a bad and corrupt act figuratively. But literally speaking, we decay when we commit idolatry.

I would like to discuss a form of idolatry which we might not commit individually, but communally. In our generation, the thoughts of sex, video games, Facebook, and so on would cross our minds when we think about idolatry. But I'm not interested in discussing these. What I'm more interested in discussing is our idolatry towards certainty. As Reformed Christians, we tend to idolize on certainty: we so desire and pursue certainty that we cannot sit still without holding on it.

To explain this further, I'd like to bring you on a brief detour. Jonathan Merritt, a liberal and gay Biblical scholar and linguist, wrote a book, stating one interesting thing about the conservatives, which we must take very seriously. He proposed that the problem with the conservatives and evangelists is that we perform what he refers to as linguistic fossilization. We tend to lock linguistic and theology, we consider our Bible a dictionary by locking the definition of a word we find in the Bible with a certain meaning. For instance, if I ask you now, "what is a sin?", your immediate answer as a Reformed Christian would be a dictionary/textbook definition. I would not expect you to answer, "sin is when one day Adam and Eve committed so and so". The answer I expect from you would be, "sin is hamartia, which means missing the target". But now I invite you to see how Jesus answered the crowd's questions which demand him to answer in precision and certainty. A person would ask Him, "LORD, should we do A or B?", and His answer would be, "there's this parable...". Notice that the Bible does not use much of the dictionary definition approach, but a narrative story approach. A story is indirect and imprecise. Merritt warned that we have fallen into this dictionary definition extreme, for our approach towards the Bible shows how we often consider theology as a "precise" matter.

All the voices in the Bible speak in unison. And when we find a definition that goes against this unison voice, we would open our eyes widely, and march with our torches to confront. Imagine if one of our church deacons proposes to change the definition of justification. We would not respond, "what is this insight you wish to share with us?", we would immediately protest, "what are you doing?!". Or how some of you could not accept what I delivered during last week's Bible Study about historical accuracy (see discussion here: http://look-ing-up.blogspot.com/2019/03/deuteronomic-history-vic-jethro-rachmadi.html).

The Bible is not a dictionary, in fact, according to Merritt, if we pay good attention to the Bible, we could find multiple variations derived from a single term. Merritt cited a non-controversial evangelical scholar, Gary Anderson, who wrote "Sin: A History", which consists of the multiple definitions of sin throughout history. Anderson suggests three concepts behind the term sin. The first which he wrote was the concept of sin being an adhering stain which must be cleansed. He also introduced the concept of sin being a burden/weight, which ends with the concept of cleansing and the sacrifice of atonement in the Jewish custom according to the Old Testament. They committed a communal stain, and annually, the great priest would place his hands on a scapegoat which will be excommunicated. That goat would carry the burden of the whole nation. Then you move forward to the New Testament to find how during the Roman Empire, the Romans brought a barbaric and business-oriented culture into the world. Business, economy, and marketing became well-known during this period. That later, we find that Paul defined sin in terms of debts, which is a marketing term. Alike, "the wage of sin is death" (Rom 6:23) also describes sin in light of the Roman business culture.

So, if you could bring Paul back to the Old Testament with a time machine, the high priests would be alarmed with Paul's understanding of sin. Thus we can say that the Bible contains a definition evolution in a certain understanding. This does not only occur in the Bible but also when you see the life of the church congregants after the canon was accomplished.

Paying close attention to Jesus' teaching, He also used marketing terms such as "but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven" (Matt 6:20a). A more accurate translation of this verse is to invest for yourselves treasures in heaven. And it's interesting that this concept is passed on all the way to the pre-reformation era when indulgences (indulgencia) was being sold. Indulgencia is to pay right here on earth, to invest in the heavenly treasure. And this heavenly treasure for them was to save their family members suffering in the purgatory fire. They took Paul's concept of sin and made it literal and universal.

Then came reformation and this definition was annihilated, replaced with various other definitions. This is because ever since the protestant arrived, the church has many voices: the Baptist, Orthodox, Reformed, and so on. And today, we see that we are using this reimagination too, that we are part of the linguistic evolution.

In the modern era of the 20th-21st century, somebody used a rhetorical language, "you have a problem of sin and what you need is a Savior". There has got to be a solution to a problem. And you cannot find this during the revolution nor Paul's periods. It's interesting to know that regardless our conscience, we are part of the definition/terminology evolution (re-imagination) of the Bible.

What comes to you your mind when I mentioned the term "re-imagination" in the church? We do not realize that we all are part of the re-imagination. In fact, this is the work of the reformers, they redefine terminologies.

In addition, it is not uncommon to find such redefinition in the linguistic field. Language evolves in time, otherwise, it will be called a dead language. CS Lewis was a literature professor, and he described language as a tree, which trunk consists of an inner ring. The question "what is a sin?" is the trunk, but how do we know that that tree is alive? Answer: the leaves will fall, branches will emerge from that trunk. Similarly, we know whether or not a language is alive from its linguistic evolution.

If you have studied or are studying in a seminary, then you will be required to learn the Greek and Hebrew languages. But if you speak these languages in Greece and Israel today, nobody would be able to comprehend you, because these languages are alive and continue to evolve in time.

To discuss the Bible is not the truth in and of itself, but merely a means of the truth, a way to get to the truth. Viewing the Bible as a dead language would make our exegesis an autopsy of a dead body. I, as a speaker, would merely become an observer of this dead creature, reporting my findings to you all. Changes become inevitable when we are engaging relationally with a living thing.

What I would like us to learn today is not merely a linguistic understanding, but the reason behind our unacceptance when we hear about changes and uncertainties in the Bible.

Albert Schweitzer might be right when he referred to Jesus' response, "but who do you say that I am?" (Matt 16:15), as refreshing, because it is dangerous to lack plurality in discussing theology. Back to our example of "what is a sin?". Some connote sin with illness, but where in the Bible is this idea implied? The Bible very rarely uses medical terms. But maybe there is one verse which this concept is based on, "Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. I have not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance" (Luke 5:31-32). We then take this single verse and assume the concept universally. But when a murderer (a sinner) is brought to you, would you begin to connote his transgression with an illness? Language is a means, and never the truth itself. And language is not a means of precision/certainty, but a means of approximation (approach). So, is understanding sin as an illness correct? Yes, because sin possesses the attributes of an illness. For instance, sin is contagious. Others hurt you, and therefore you have the urge to do the same to others. But what if we take this concept and universalize it? What about murder? What about those who are ill physically? Does his sin cause his illness? Could be, but generally speaking, you cannot approach a person suffering from cancer saying, "you have caused your own tragedy". And you would definitely not imprison this cancerous person, the way you would imprison a murderer. Therefore, a concept could be right, but it cannot be universalized, and plurality is a necessity.

And have you noticed how this plurality does not stop to the present time, but will also continue to the future? Could we accept that in the future, there will be newborn generations and they will try to redefine these Biblical terms to definitions we could never have thought of? Or maybe as a community, we have been holding onto an idol called certainty? Upon encountering an unfixed language in the Bible, our follow up response would be, "how do we know whether this is a correct, Christian understanding if every generation could reinterpret the language of the Bible?" Maybe the answer to this is that maybe we can't. Our pursuit of certainty would mean that we believe that our truth depends on the others' errors.

Sometimes, we hear a rhetorical question in a Reformed church, "why must there be a Reformed Evangelical Church?", which is commonly responded by, "because Christianity has been corrupted by the charismatics and liberals". A Reformed pastor I know then said, "if Reformed Evangelical Church must stand to respond to the charismatics movement, then there will no longer be a Reformed Evangelical Church when the charismatics no longer exist". The concept of I know who I am because I know that others are wrong is wrong. Your truth must not depend on others' errors. As conservatives and evangelists, we often test this certainty. When we are attacked by the LGBT community and the liberals, "the law of LGBT is not mentioned in the Bible", we would immediately and in panic attempt to lock Biblical terms so that Christianity is conserved. I am against the LGBT, but what I would like to imply here is that as conservatives, we tend to perform fossilization of the Bible, not giving it room to grow for the sake of preserving life. Ironically, this very concept leads to death.

Returning to the concept idolatry as a corrupt and decaying act. Merritt provided undeniable data: the US is very much influenced by the Evangelical Conservatives, in terms of financial as well as population. 71% of the US citizens identify themselves as Christians, yet only 7% of them admit praying to God outside the church. If the same polling is given to church attendees, this number would increase to 13%. Only 13% of the US citizens who attend church services weekly pray outside the church. So, 7 out of 8 church attendees in the US do not pray until the following week they attend church. Merritt highlighted this data because language is a means of our prayer to God. He suggests that Christianity would die if we continue to lock our prayer into a mantra we could memorize and lock into precision. The more we attempt to lock in our prayers, the more people will stop praying. Similarly, Latin used to be the language of liturgy, a language used specifically to address God, and Latin has become a dead language now. We think locking something into precision is a way for us to survive from the attacks out there, but in the US, this is the very reason that kills Christianity, as they give no room for interaction.

In a Reformed church, why do we feel like our prayers have turned stale and dry? Maybe as a community, we are addicted to certainty, and this kills our spirituality. What is the solution then? It depends on what you mean by a solution. If you seek certainty, then we would be back to our initial problem. The problem is not what we must do, but sometimes we know too much of what we must do. It is not that we do not know much about God, but sometimes we know of God too precisely. Maybe this is what we are fond of in the Reformed church, we are in a mad pursuit of a precise answer, leaving no room for mystery. The solution is not to find a certain solution, but to realize that this problem is not to be solved, but to be managed. For example, in the medical field, the term managing the pain is often used (the pain is called to be managed if the pain is incurable). In managing the pain, we must open our ears for others, even if they believe in a different theology than us. If an LGBT person comes up to you and says, "I'm a Christian and I'm gay", do not immediately close your ears because you merely think that they are heretical. I do not support the LGBT community myself, nor does the Bible, but this is not a matter of agreeing and disagreeing, but whether we are willing to open our ears for them.

The Biblical model of our faith is not in a precise answer, but in asking questions. The definition of faith in Greek is the foundation of all things we hope. Faith seems to be hovering on an unknown plane, but I am not implying that faith has no foundation, of course, it does. But even according to the Greek, the model of faith holds a big question mark: faith is unheld, unseen, full of struggles, uncertain, ungrasped.

What if continuing to ask and struggle in questions is what it means to be a faithful man? What if faith becomes a means not to get answers, but to acquire questions?

Is collecting precise definitions really a way to obtain faith? Faith means to follow God, despite our lack of understanding and our limitation to fathom Him.

Lastly, when speaking of theology, we must also open our ears to our opposites: women, oppressed people, LGBT, the charismatics, the liberals, and so on. It is in opening our ears to them that we may grow, rather than holding onto our "precise and timeless faith", as if dwelling with a dead body.

FIRE

A faith that is full of answers will lead you to death. For once you have collected your answers, you would fall into slumber. But what sets you ablaze are questions. I preached about Jonah and the Tree of Knowledge in the youth fellowship last week. There was a question that arose, "if God is omniscient (all-knowing), then He knew that men will fall, but why did He still place the tree as a test? Was God evil? Or God could have said to Adam and Eve, "I will send you a link entitled History for Dummies, which contains a video of what will happen after you eat the forbidden fruit. There will be the Holocaust, Hitler, Stalin, etc", then Adam and Eve would never have eaten the fruit."

Our usual answer would be, "God did it out of love, and God wanted them to obey Him out of love, and not fear of the terrible things that will happen in the future". Yet, this answer does not make you want to pray to God. A more correct answer would be, "you're right, God knew that men would fall and that He Himself had to pay for it, but why did He decide to tread that road still? He knew that the world would rebel against Him, destroy His creations, and even those whom He would redeem would not be thankful, would not understand His grace, would demand a fixed certainty from those theology books. He knew all of these, didn't He? But why did He do it still?"

Do you see the difference between a theology that ends with an answer (certainty) and a question? Which response makes you want to pray to Him more? This is what challenges us today: why did He do it still?

Let us open to Deuteronomy 4:15-34

Covenental life is a central topic in the lives of chosen people, and it is an important basis in Deuteronomy. In this part, we will discuss what God means by a covenant. It is important for us to explore this concept repetitively because we tend to extreme our relationship to either side of the poles. A covenant is a covenantal relationship, which involves two or more parties, consisting of both relational and covenantal aspects. Yet we often separate these two concepts in our daily application. When we sign a contract, we assume that both parties do not have any personal relationship. A personal relationship for us consists of freedom and spontaneity and is absent from regulated rules jotted down on a written contract. But the Bible says that a covenant transcends this narrow category. For in Deuteronomy, we see that our relationship with God is so intimate and private, and yet our demands exceed those of a professional contract. Therefore, we must understand our relationship with God along with its complexity.

Moses used three pictures to show this concept clearly. We always connote our relationship with God with love and faithfulness, but in this part of the scripture, we see jealousy, perversion (idolatry), and consuming fire. Through these three points, we will discuss more in depth about our relationship with God.

JEALOUSY

Richard Dawkins claimed that Christianity must be disposed of, because of this annoying "fictional" character described in Deuteronomy 4:21-24. Not only is He a jealous character, but He takes pride in His jealous attribute. Before we move on, we have to be able to differentiate between jealousy and envy. To envy is to covet (egoistic), but to be jealous is to be possessive (also egoistic and self-centered). The difference is that to envy, is to covet something that others own, but to be jealous is to be possessive towards what one owns. Therefore, the Hebrew and Greek Bible use the terms envy and jealousy interchangeably (Hebrew: qannah/qinnah; Greek: zelos).

Is God's jealousy here the same as envy then? Did Dawkins speak of truth? Is God depicted as an annoying character here? Absolutely not. There is a distinct difference in the Hebrew language. Our differentiating tool is phenomena, while the Hebrew's differentiating tool is in who does it. Though based on the same root word, qinnah is used specifically for human (mentioned 32-44 times in the Bible), while qannah is for God (mentioned 6 times in the Bible). The Bible's differentiating tool is not in its phenomena or the jealousy level a person possesses but in the doer. Therefore, we ought not to view God's jealousy as a negative concept. After all, the positivity in our jealousy is very evident. What kind of jealousy is positive? As parents, when we see our children behaving badly, we rise to anger, which is caused simply by our love towards them. It is easier to explain this in the English language because they have the terms for and against. For instance, are you for or against the nuclear plant? When we are jealous of a person, what is important is to ask the question of whether we are angry with that person, or angry for that person.

Anger is not a sin in and of itself, for anger does not collide with a relationship. If you are engaged in a relationship, you will experience anger. If you have never been angry with a person, it means you do not have any relationship with him. The opposite of love is not anger nor hate, but apathy.

Why then does the picture of anger in our daily life so different than the anger Bible depicts? Because we have never seen true love. Being in our sinful nature, our love is stained with self-centeredness, as we love others to fulfill our personal needs. We are often more hungry than being in love. We could love something immensely, but only for us to consume. If you truly love a tree, you would not loot its twigs, fruits, and wood, but you would water it. Therefore, it is impossible for us human to create positive jealousy, because our anger is always because of the object, and not for the object. We rise to anger because their sins humiliate and inflict us.

Thus, the classification is not between envy and jealousy, but in the doer. The aspect of corruptness is ever present when we are jealous, not because there is absolutely no aspect of angry for the object, but because there is always an aspect of anger because of the object.

Yet God's jealousy purely consists of anger for those whom He loves. We must be thankful if our relationship with God is full of God's anger because it only shows how much He cares and loves you. CS Lewis wrote that a God who is never satisfied with you only shows that He is a God who loves you, like an artist who considers his art always lacking and in need of correction. God is never satisfied. Demanding a God who could be satisfied is demanding Him to stop loving us.

Now you have seen how positive God's jealousy is. The drop rate in a theological seminary is the highest among all schools. In my previous accreditation, my professor told me that the drop rate of 20-25% in a theological seminary is very common. But in our theological seminary, there must usually be a mistake or a sin which a dropped out student committed during his study, and very rarely due to health issue problem. And every time there was a student being dropped out, the other students would weep, not because of his sins, but our sins. It did not matter what the dropped out student did, what mattered most was the fact that we were aware of his sins since the beginning and refused to confront him. And we did not confront him not because we fear to offend him, but because we simply did not care. Or frankly speaking, our care towards our own feelings mattered more than our care towards him.

Hence, God's jealousy towards men is a significant declaration. God is very committed to our well-being. This is the first point.

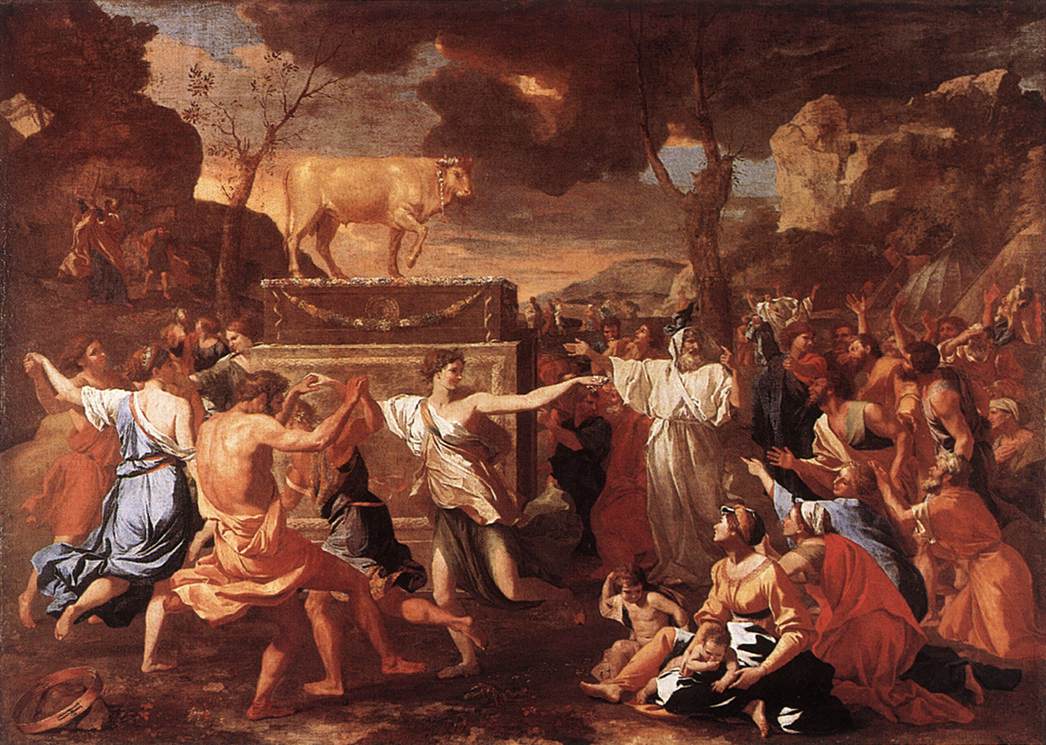

|

| The Adoration of the Golden Calf, by Nicolas Poussin |

IDOLATRY

This second point is mentioned frequently throughout verses 15-23. But before we dig deeper into those verses, we have to set one thing straight: verses 16-19 are especially interesting, this part reminds us of what idolatry is. The purpose of these verses is to show what could be considered gods, and the answer is everything! The purpose of these verses is not to instruct what we should not create, but to instruct that we should not create everything from A to Z. Verse 19 gives an interesting definition, "an idol is not just everything, but something that is God-given". Meaning, an idol is actually something good, because all things God-given is good. In fact, it is a good thing that could be transformed into an idol, and the better it is, the better the idol it will make.

For example, in disciplining your child, you remind them not to play video games for hours so that they would be the number one in their class and become an achiever. Yet, according to the Bible, this aspiration to be the number one and to be an achiever could even be a better idol than hours playing the video game. When your child is all grown up, performance and ranking become his life's goal, by doing so, he abandons his wife and children, he belittles relationships that do not benefit him, all these for the sake of his performance. Because when he plays video games, everyone around him despises his action, and he knows himself that his addiction to video games is bad. Contrarily, by becoming a workaholic, many companies would contact him, offering him jobs. Let this be a reminder for us all that idolatry is not in the object, but about where we rank that object within our hearts. Augustine introduced the idea of ordo amoris (the order of love). If we place the object we love higher than God in our ordo amoris, and if it fills our life, replacing God's position, the object has become our idol. Read more about ordo amoris here: http://look-ing-up.blogspot.com/2017/09/a-double-victory.html.

Idolatry is when we consider an object to be most effectual in our lives, including most effectual in creating grief and resentment. Your idol is not only something that delivers you the most joy, but also something that delivers you the most resentment. Your idol is the most effectual object in your life as it places the highest ranking in your ordo amoris.

The next point which I wish to share is how Moses stated idolatry as a corrupt act (verse 16), which in Indonesian is translated as a decaying act. Idolatry destroys and decays us. We like to think that Moses used this term merely as a metaphorical language, that committing idolatry is a bad and corrupt act figuratively. But literally speaking, we decay when we commit idolatry.

I would like to discuss a form of idolatry which we might not commit individually, but communally. In our generation, the thoughts of sex, video games, Facebook, and so on would cross our minds when we think about idolatry. But I'm not interested in discussing these. What I'm more interested in discussing is our idolatry towards certainty. As Reformed Christians, we tend to idolize on certainty: we so desire and pursue certainty that we cannot sit still without holding on it.

To explain this further, I'd like to bring you on a brief detour. Jonathan Merritt, a liberal and gay Biblical scholar and linguist, wrote a book, stating one interesting thing about the conservatives, which we must take very seriously. He proposed that the problem with the conservatives and evangelists is that we perform what he refers to as linguistic fossilization. We tend to lock linguistic and theology, we consider our Bible a dictionary by locking the definition of a word we find in the Bible with a certain meaning. For instance, if I ask you now, "what is a sin?", your immediate answer as a Reformed Christian would be a dictionary/textbook definition. I would not expect you to answer, "sin is when one day Adam and Eve committed so and so". The answer I expect from you would be, "sin is hamartia, which means missing the target". But now I invite you to see how Jesus answered the crowd's questions which demand him to answer in precision and certainty. A person would ask Him, "LORD, should we do A or B?", and His answer would be, "there's this parable...". Notice that the Bible does not use much of the dictionary definition approach, but a narrative story approach. A story is indirect and imprecise. Merritt warned that we have fallen into this dictionary definition extreme, for our approach towards the Bible shows how we often consider theology as a "precise" matter.

All the voices in the Bible speak in unison. And when we find a definition that goes against this unison voice, we would open our eyes widely, and march with our torches to confront. Imagine if one of our church deacons proposes to change the definition of justification. We would not respond, "what is this insight you wish to share with us?", we would immediately protest, "what are you doing?!". Or how some of you could not accept what I delivered during last week's Bible Study about historical accuracy (see discussion here: http://look-ing-up.blogspot.com/2019/03/deuteronomic-history-vic-jethro-rachmadi.html).

The Bible is not a dictionary, in fact, according to Merritt, if we pay good attention to the Bible, we could find multiple variations derived from a single term. Merritt cited a non-controversial evangelical scholar, Gary Anderson, who wrote "Sin: A History", which consists of the multiple definitions of sin throughout history. Anderson suggests three concepts behind the term sin. The first which he wrote was the concept of sin being an adhering stain which must be cleansed. He also introduced the concept of sin being a burden/weight, which ends with the concept of cleansing and the sacrifice of atonement in the Jewish custom according to the Old Testament. They committed a communal stain, and annually, the great priest would place his hands on a scapegoat which will be excommunicated. That goat would carry the burden of the whole nation. Then you move forward to the New Testament to find how during the Roman Empire, the Romans brought a barbaric and business-oriented culture into the world. Business, economy, and marketing became well-known during this period. That later, we find that Paul defined sin in terms of debts, which is a marketing term. Alike, "the wage of sin is death" (Rom 6:23) also describes sin in light of the Roman business culture.

So, if you could bring Paul back to the Old Testament with a time machine, the high priests would be alarmed with Paul's understanding of sin. Thus we can say that the Bible contains a definition evolution in a certain understanding. This does not only occur in the Bible but also when you see the life of the church congregants after the canon was accomplished.

Paying close attention to Jesus' teaching, He also used marketing terms such as "but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven" (Matt 6:20a). A more accurate translation of this verse is to invest for yourselves treasures in heaven. And it's interesting that this concept is passed on all the way to the pre-reformation era when indulgences (indulgencia) was being sold. Indulgencia is to pay right here on earth, to invest in the heavenly treasure. And this heavenly treasure for them was to save their family members suffering in the purgatory fire. They took Paul's concept of sin and made it literal and universal.

Then came reformation and this definition was annihilated, replaced with various other definitions. This is because ever since the protestant arrived, the church has many voices: the Baptist, Orthodox, Reformed, and so on. And today, we see that we are using this reimagination too, that we are part of the linguistic evolution.

In the modern era of the 20th-21st century, somebody used a rhetorical language, "you have a problem of sin and what you need is a Savior". There has got to be a solution to a problem. And you cannot find this during the revolution nor Paul's periods. It's interesting to know that regardless our conscience, we are part of the definition/terminology evolution (re-imagination) of the Bible.

What comes to you your mind when I mentioned the term "re-imagination" in the church? We do not realize that we all are part of the re-imagination. In fact, this is the work of the reformers, they redefine terminologies.

In addition, it is not uncommon to find such redefinition in the linguistic field. Language evolves in time, otherwise, it will be called a dead language. CS Lewis was a literature professor, and he described language as a tree, which trunk consists of an inner ring. The question "what is a sin?" is the trunk, but how do we know that that tree is alive? Answer: the leaves will fall, branches will emerge from that trunk. Similarly, we know whether or not a language is alive from its linguistic evolution.

If you have studied or are studying in a seminary, then you will be required to learn the Greek and Hebrew languages. But if you speak these languages in Greece and Israel today, nobody would be able to comprehend you, because these languages are alive and continue to evolve in time.

To discuss the Bible is not the truth in and of itself, but merely a means of the truth, a way to get to the truth. Viewing the Bible as a dead language would make our exegesis an autopsy of a dead body. I, as a speaker, would merely become an observer of this dead creature, reporting my findings to you all. Changes become inevitable when we are engaging relationally with a living thing.

What I would like us to learn today is not merely a linguistic understanding, but the reason behind our unacceptance when we hear about changes and uncertainties in the Bible.

Albert Schweitzer might be right when he referred to Jesus' response, "but who do you say that I am?" (Matt 16:15), as refreshing, because it is dangerous to lack plurality in discussing theology. Back to our example of "what is a sin?". Some connote sin with illness, but where in the Bible is this idea implied? The Bible very rarely uses medical terms. But maybe there is one verse which this concept is based on, "Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. I have not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance" (Luke 5:31-32). We then take this single verse and assume the concept universally. But when a murderer (a sinner) is brought to you, would you begin to connote his transgression with an illness? Language is a means, and never the truth itself. And language is not a means of precision/certainty, but a means of approximation (approach). So, is understanding sin as an illness correct? Yes, because sin possesses the attributes of an illness. For instance, sin is contagious. Others hurt you, and therefore you have the urge to do the same to others. But what if we take this concept and universalize it? What about murder? What about those who are ill physically? Does his sin cause his illness? Could be, but generally speaking, you cannot approach a person suffering from cancer saying, "you have caused your own tragedy". And you would definitely not imprison this cancerous person, the way you would imprison a murderer. Therefore, a concept could be right, but it cannot be universalized, and plurality is a necessity.

And have you noticed how this plurality does not stop to the present time, but will also continue to the future? Could we accept that in the future, there will be newborn generations and they will try to redefine these Biblical terms to definitions we could never have thought of? Or maybe as a community, we have been holding onto an idol called certainty? Upon encountering an unfixed language in the Bible, our follow up response would be, "how do we know whether this is a correct, Christian understanding if every generation could reinterpret the language of the Bible?" Maybe the answer to this is that maybe we can't. Our pursuit of certainty would mean that we believe that our truth depends on the others' errors.

Sometimes, we hear a rhetorical question in a Reformed church, "why must there be a Reformed Evangelical Church?", which is commonly responded by, "because Christianity has been corrupted by the charismatics and liberals". A Reformed pastor I know then said, "if Reformed Evangelical Church must stand to respond to the charismatics movement, then there will no longer be a Reformed Evangelical Church when the charismatics no longer exist". The concept of I know who I am because I know that others are wrong is wrong. Your truth must not depend on others' errors. As conservatives and evangelists, we often test this certainty. When we are attacked by the LGBT community and the liberals, "the law of LGBT is not mentioned in the Bible", we would immediately and in panic attempt to lock Biblical terms so that Christianity is conserved. I am against the LGBT, but what I would like to imply here is that as conservatives, we tend to perform fossilization of the Bible, not giving it room to grow for the sake of preserving life. Ironically, this very concept leads to death.

Returning to the concept idolatry as a corrupt and decaying act. Merritt provided undeniable data: the US is very much influenced by the Evangelical Conservatives, in terms of financial as well as population. 71% of the US citizens identify themselves as Christians, yet only 7% of them admit praying to God outside the church. If the same polling is given to church attendees, this number would increase to 13%. Only 13% of the US citizens who attend church services weekly pray outside the church. So, 7 out of 8 church attendees in the US do not pray until the following week they attend church. Merritt highlighted this data because language is a means of our prayer to God. He suggests that Christianity would die if we continue to lock our prayer into a mantra we could memorize and lock into precision. The more we attempt to lock in our prayers, the more people will stop praying. Similarly, Latin used to be the language of liturgy, a language used specifically to address God, and Latin has become a dead language now. We think locking something into precision is a way for us to survive from the attacks out there, but in the US, this is the very reason that kills Christianity, as they give no room for interaction.

In a Reformed church, why do we feel like our prayers have turned stale and dry? Maybe as a community, we are addicted to certainty, and this kills our spirituality. What is the solution then? It depends on what you mean by a solution. If you seek certainty, then we would be back to our initial problem. The problem is not what we must do, but sometimes we know too much of what we must do. It is not that we do not know much about God, but sometimes we know of God too precisely. Maybe this is what we are fond of in the Reformed church, we are in a mad pursuit of a precise answer, leaving no room for mystery. The solution is not to find a certain solution, but to realize that this problem is not to be solved, but to be managed. For example, in the medical field, the term managing the pain is often used (the pain is called to be managed if the pain is incurable). In managing the pain, we must open our ears for others, even if they believe in a different theology than us. If an LGBT person comes up to you and says, "I'm a Christian and I'm gay", do not immediately close your ears because you merely think that they are heretical. I do not support the LGBT community myself, nor does the Bible, but this is not a matter of agreeing and disagreeing, but whether we are willing to open our ears for them.

The Biblical model of our faith is not in a precise answer, but in asking questions. The definition of faith in Greek is the foundation of all things we hope. Faith seems to be hovering on an unknown plane, but I am not implying that faith has no foundation, of course, it does. But even according to the Greek, the model of faith holds a big question mark: faith is unheld, unseen, full of struggles, uncertain, ungrasped.

What if continuing to ask and struggle in questions is what it means to be a faithful man? What if faith becomes a means not to get answers, but to acquire questions?

Is collecting precise definitions really a way to obtain faith? Faith means to follow God, despite our lack of understanding and our limitation to fathom Him.

Lastly, when speaking of theology, we must also open our ears to our opposites: women, oppressed people, LGBT, the charismatics, the liberals, and so on. It is in opening our ears to them that we may grow, rather than holding onto our "precise and timeless faith", as if dwelling with a dead body.

FIRE

A faith that is full of answers will lead you to death. For once you have collected your answers, you would fall into slumber. But what sets you ablaze are questions. I preached about Jonah and the Tree of Knowledge in the youth fellowship last week. There was a question that arose, "if God is omniscient (all-knowing), then He knew that men will fall, but why did He still place the tree as a test? Was God evil? Or God could have said to Adam and Eve, "I will send you a link entitled History for Dummies, which contains a video of what will happen after you eat the forbidden fruit. There will be the Holocaust, Hitler, Stalin, etc", then Adam and Eve would never have eaten the fruit."

Our usual answer would be, "God did it out of love, and God wanted them to obey Him out of love, and not fear of the terrible things that will happen in the future". Yet, this answer does not make you want to pray to God. A more correct answer would be, "you're right, God knew that men would fall and that He Himself had to pay for it, but why did He decide to tread that road still? He knew that the world would rebel against Him, destroy His creations, and even those whom He would redeem would not be thankful, would not understand His grace, would demand a fixed certainty from those theology books. He knew all of these, didn't He? But why did He do it still?"

Do you see the difference between a theology that ends with an answer (certainty) and a question? Which response makes you want to pray to Him more? This is what challenges us today: why did He do it still?

February 27th, 2019

By Vik. Jethro Rachmadi B.Mus., M.Th., GRII Kelapa Gading

Written by Alicia Angie Wiranata

Alice

This sermon note has not been revised by the preacher.

By Vik. Jethro Rachmadi B.Mus., M.Th., GRII Kelapa Gading

Written by Alicia Angie Wiranata

Alice

No comments:

Post a Comment